Nurse-Centered Shift Planning

Nurse-Centered Shift Planning

Nurse-Centered Shift Planning

Shift work causes many problems in the lives of nurses. It leads to several health issues, such as insomnia, digestive problems, and burnout. In addition, shift work disturbs nurses' social life. They often have to work on weekends or public holidays, when other people spend time with friends and family.

Previous research indicated that some of these negative effects can be avoided if we give nurses more control in shift planning, so they can better integrate their work and leisure times. This can have positive effects, but often at the cost of efficiency. Many systems that give nurses more control rely on mostly manual planning. Automatic, computer-based approaches can be more efficient, but they usually exclude nurses from planning. So in the past, healthcare teams had to choose between either nurse control or efficiency. But they could not have both.

In the "GamOR" project, we developed a nurse-centered shift planning system to combine the two. We tried to find the right way to combine nurse control with automation. Our design process was focused on maintaining or increasing nurses' subjective well-being and fairness in a computer-supported planning system. Most of my research focused on understanding the nurse perspective in specific planning situations. Computer support was only integrated where it seemed meaningful and did not interfere with the primary goals, well-being and fairness.

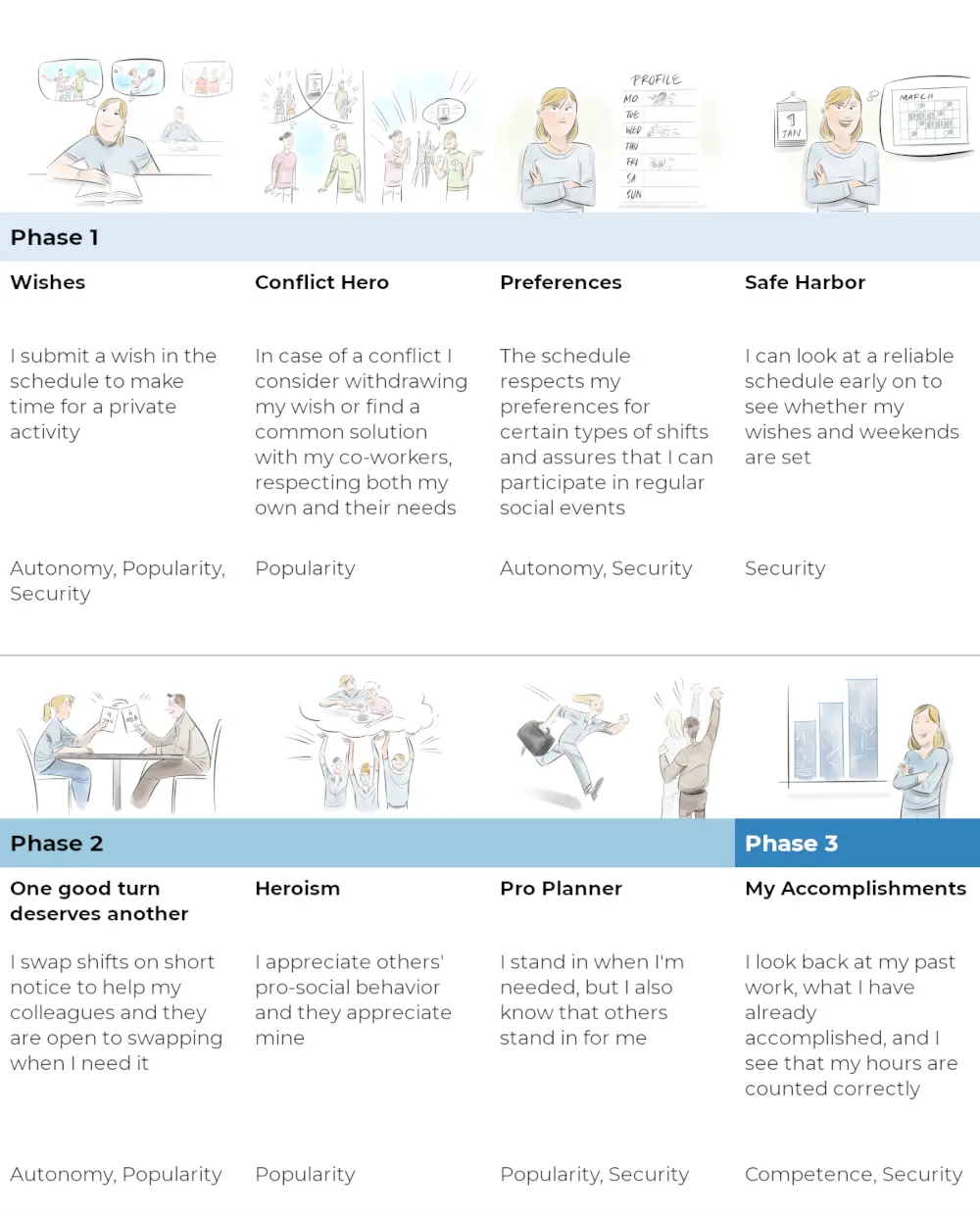

We have described the process in detail in one of our publications. But briefly put, in our nurse-centered shift planning approach, nurses can submit "wishes" for free shifts that are directly integrated in the shift plan. They are not considered as "suggestions", but as top priority requirements. Of course, sometimes not all wishes can be integrated, for example on Christmas or other unpopular shifts where many nurses want time off. In such cases, our system relies on a direct, in-person negotiation process between everyone involved. This way nurses have all the flexibility to find a workable solution that we directly include in the shift plan. Everything else, such as all wishes that do not collide, will be planned automatically. This reduces nurses' workload.

This partially manual process acknowledges three findings from our research. First, direct involvement in decision-making is an important part of nurses' fairness experiences, which means that such decisions should not be made automatically. Second, the quality of manual solutions can in some cases be higher than everything a computer can find automatically. And third, it assures that nurses agree on the solution. Automatic decisions that nurses' do not agree with can cause other problems down the road. The nurses can find their ways around a bad "official" plan. They may call in sick, make informal agreements among each other, or start to use the software in unintended ways. They may also be less willing to stay in their job much longer. In that sense, giving high priority to nurses' needs and wishes makes sense not only from the worker perspective, but also for the management.

In contrast, the partial automation is also helpful. Nurses know that they work in shifts, and they accept some flexibility on regular days. Our findings indicate that they usually do not need to control every single shift in a month, but they care about certain shifts that are important to them. With our system, they have control about everything they consider important, but the rest is done automatically with all sorts of considerations (e.g., general preferences for morning/afternoon shifts, regular appointments such as sport clubs, individual contracts etc.).

Our nurse-centered shift planning system was a finalist for the UX Design Awards 2019. It led to several presentations and publications (see below), including my PhD Thesis.

Publications and Resources

A Nurse-Centered Approach to Computer-Supported Healthcare Shift Planning

Uhde (2023)

PhD Thesis, University of Siegen

pdfFairness and Decision-making in Collaborative Shift Scheduling Systems

Uhde, Schlicker, Wallach & Hassenzahl (2020)

In this paper we focused on subjective fairness from the nurse perspective. The main findings include that fairness in conflict resolutions is based on individual needs, not equality or performance measures. We also confirmed that including nurses in the decision-making process leads to higher process fairness.

pdf videoDesign and Appropriation of Computer-Supported Self-Scheduling Practices in Healthcare Shift Work

Uhde, Laschke & Hassenzahl (2021)

This paper describes the worker-centered design process of our hybrid shift planning system, and a nine-month field study of a functional prototype in a retirement community. Our findings suggest that nurses do not approach shift planning with a competitive mindset, but instead consider their co-workers' needs and wishes in their planning practices. Instead of focusing on conflict resolution between nurses' wishes, we argue that a focus on negotiation and conflict prevention could lead to better shift planning systems.

pdf videoExperiential Benefits of Interactive Conflict Negotiation Practices in Computer-Supported Shift Planning

Uhde, Laschke & Hassenzahl (2022)

During the previous field study, we had found several practices nurses developed to prevent conflicts from happening in the first place. But can such practices have a positive effect on well-being and fairness? In this paper we compared the nurses' interactive conflict negotiation practices with a fully automated alternative. We found positive effects on all measures, including affect, need fulfillment, fairness, and nurses' expectations of long-term team spirit. This confirms the positive effects of interactive shift planning on nurses.

pdfContext Factors for Pro-social Practices in Healthcare

Uhde, Mesenhöller & Hassenzahl (2021)

Throughout the project, we frequently found that the team spirit plays a crucial role in shift planning. If colleagues get along with each other, they tend to be more cooperative during conflict negotiations. This short paper explored different opportunities of creating positive team spirit through pro-social practices in healthcare settings beyond shift planning itself.

pdfOrganizing Healthcare Work: Challenges and Opportunities in Worker-Centered Shift Planning

CHIWORK Symposium (2022)

A conversation with Shadan Sadeghian in which we talk about the GamOR project and what we could learn from it about worker-centered healthcare shift planning.

videoNachhaltige Motivation durch wohlbefindensorientierte Gestaltung

Schlicker, Uhde, Hassenzahl & Wallach (2020)

A summary of the GamOR project (in German), with a focus on user research and interface design.

pdf